Thursday, November 19, 2009

Monday, September 14, 2009

Saturday, September 12, 2009

Friday, September 11, 2009

Thursday, September 10, 2009

Friday, July 10, 2009

Wednesday, July 8, 2009

Sunday, June 21, 2009

Thursday, June 4, 2009

Ridiculous

Monday, June 1, 2009

Thursday, February 19, 2009

Architecture and narrative

Architecture and Narrative The Formation of Space and Cultural Meaning, Sophia Psarra, Routledge, UK

Architecture is often seen as the art of a thinking mind that arranges, organises and establishes relationships between the parts and the whole. It is also seen as the art of designing spaces, which we experience through movement and use. Conceptual ordering, spatial and social narrative are fundamental to the ways in which buildings are shaped, used and perceived. Examining and exploring the ways in which these three dimensions interact in the design and life of buildings, this intriguing book will be of use to anyone with an interest in the theory of architecture and architecture's relationship to the cultural human environment.

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

Losing face

In view of this preliminary transformation, the Stirling Staatsgalerie might be said to be already a second-degree version of the Schinkel prototype, operating on Schinkel by way of his modernist re-interpretation. One might extend Rowe’s comment logically to read a “palace of Assembly without a facade.” this Stirling’s central circular volume would be at once a memory of the Pantheon rotunda and of an empty assembly hall; the ramp would already be included in the elements of the project; the three-sided U of offices already subsituted for the courtyard parti; the entrance already off center, and most importantly, the rear wall of the “stoa” already eroded into a screen.Schinkel's Altes Museum plan

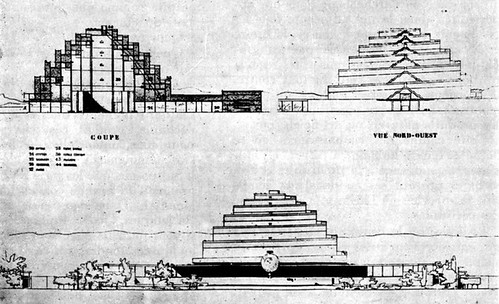

Such formal transformation was, as we have noted, however, already present in Musée Mondial where Le Corbusier retained a reference to Schinkel in plan while entirely reformulating the type in section. The first-floor plan of the Corbusian museum is, indeed, uncannily similar to Stirling’s own reformulation of the Schinkel. In both, a U-shaped blockframes acentral circle; in both, the original dome of the pantheon has been lifted: in the cas df the Musée Mondial, Le Corbusier has substituted the inner space of a high ppyramid; in that of the taatsgalerie, Stirling has completed its ruination, opening it to the sky. Le Corbusier himself made the point that, with the entire monument raised up on pilotis, the distinction between front and back had been erased, thus beginning the process that Stirling accomplishes bu means of the continuous public route through the site from top to bottom. In this sense, Stirling would not simply be destroying the Pantheon, or attacking Schinkel’s monumental version of history, but also gentlry criticizing the idealistic and quasi-mystical aspiration of Corbusian modernism.in The architectural uncanny, Anthony Vidler, 1992, MIT Press

In both Schinkel and Le Corbusier, as we have noted, architecture is indissolubly bound to the contents, real and ideological, of the museum. In the altes Museum, the sequence of rooms that assemble the schools of western painting in chronological order is posed against the calm Pantheon at the center that establishes the notion of ahistorical permanence; the public, semipermeable face of the stoa confirms the museum’s connection to the city. Architecture operates as both representation and instruument of the display of a nation’s history and its artistic heritage as the active ingredient of continuing cultural development. It is at once sign and agent of a living history.

Similarly, in Le Corbusier Musée Mondial, the grand route of time is extended back to prehistory and forward to the ever-expanding present, working on insert temporality and spatiality across cultures and peoples into a universalizing frame that, again, proposes history (enlarged in its scope by the sciences of anthropology, ethnology, and geology) as the foundation of the future. the central volume, or “Sacrarium”, universalizes the western Pantheon and acts again as a center for atemporality. Here too the architecture operates as a symbol and mechanism and its tied to its contents.

Sunday, January 25, 2009

Saturday, December 13, 2008

Monday, December 8, 2008

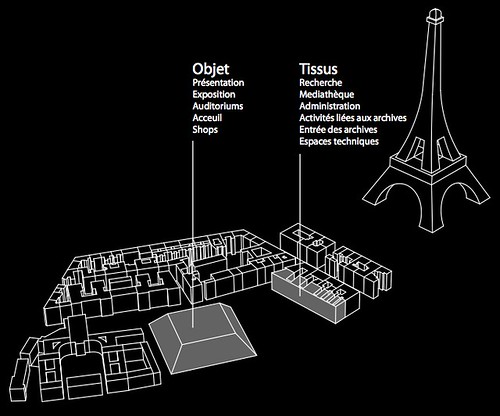

Situation

From left to right and up to down :

- Palais du Trocadéro / Musée de l'Homme

- Palais de Tokyo / Musée d'Art Moderne

- Tour Eiffel

- Musée du Quai Branly

Wednesday, December 3, 2008

Thursday, November 20, 2008

Les statues meurent aussi

Les Statues Meurent Aussi, Alain Resnais, 1950

Quand les hommes sont mort, ils entrent dans l'histoire. Quand les statues sont mortes, elles entrent dans l'art. Cette botanique de la mort, c'est ce que nous appelons la culture.C'est ainsi que commence ce documentaire controversé qui pose la question de la différence entre l'art nègre et l'art royal mais surtout celle de la relation qu'entretient l'Occident avec cet art qu'elle vise à détruire sans même s'en rendre compte. Ce n'est pas encore la vague indépendante, mais quelques prémices se font sentir dans ce film. Un saut dans le passé, une photographie du point de vue occidental.

Le film a fait l'objet d'une interdiction en France durant huit ans.

Quant à eux, ils savaient tout ce qui se passait en Afrique et nous étions même très gentils de ne pas avoir évoqué les villages brûlés, les choses comme ça ; ils étaient tout à fait d'accord avec le sens du film, seulement (c'est là où ça devient intéressant), ces choses-là, on pouvait les dire dans une revue ou un quotidien, mais au cinéma, bien que les faits soient exacts, on n'avait pas le droit de le faire. Ils appelaient ça du "viol de foule". L'interdiction eut des conséquences très graves pour le producteur. Quant à nous - est-ce un hasard ? - ni Chris Marker ni moi ne reçûmes de propositions de travail pendant trois ans.Alain Resnais, sur son entretien avec deux des représentants de la commission de censure.

Published on Wikipedia

Wednesday, November 19, 2008

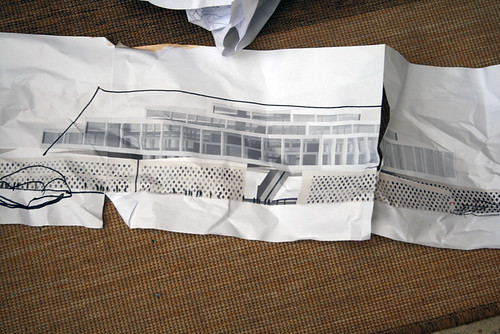

Learning from L.C. II

Learning from Corbusier. Sebastien Berthier and Michel Sikorski, Photo Samuel Guigues, 2006

Learning from Corbusier. Sebastien Berthier and Michel Sikorski, Photo Samuel Guigues, 2006Le Corbusier's spiral Labyrinth

In the archive of Le Corbusier the World Museum is a precursor (in plan diagram at least) to a set of projects, hereafter to be referred to as the spiral museums. Those designs include the scheme for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Paris (1931), project for a Museum of Unlimited Extension (1939), the Cultural Centre of Ahmenedabad Museum (1954), the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo (1957), and the Museum and Art Gallery of Chandigarh (completed in 1970). The spiral museum design also appears in the layout of urban design schemes such as the design for Rio de Janeiro (1929) and Saint-Die (1946). As a project the spiral museum occupies the archive in every decade from the 1920s until the architect’s death.Moulis, Antony, “Figure and Experience: The labyrinth and Le Corbusier’s World Museum”, Interstices No. 4 (Auckland) 1996: CD-ROM publication.

In the critical literature little is made of this occurrence, this design’s constant return, nor indeed of the spiral museum as a project within the archive. The built versions have not been considered remarkable in their own terms. What little critical interest that there is focuses upon the spiral form itself. Thus the spiral has been seen to stand for the architect’s interest in the symbolism of nature and patterns of growth and archetypal forms.

Yet the drawings from the Oeuvre Complete of the World Museum project are also manifestly setting out a promenade. This is a museum in which a spectator takes up an itinerary of history set out along a continuous wall; an itinerary carrying the spectator from the centre to edge of the museum, and it is this aspect of the design - how this promenade is being figured in the drawings - into which I inquire. In order to map out the promenade of the museum I point to a coincidence of figures - of the figure of this plan with that of a labyrinth. In literally appearing to take up the plan form of the labyrinth figure the project thus might be viewed as rehearsing the qualities of labyrinthine paradox (a recognition of a particular type of doubling)

Saturday, November 15, 2008

Permanent exhibition preview

Shift to zoom in, Ctrl to zoom out, click and drag to move in the picture

Monday, November 10, 2008

Pyramids

On ne peut pas l’entendre [la différance] et nous verrons en quoi elle passe aussi l’ordre de l’entendement. Elle se propose par une marque muette, par un monument tacite, je dirai même une pyramide, songeant ainsi non seulement à la forme de la lettre lorsqu’elle s’imprime en majeur ou en majuscule, mais à tel texte de l’Encyclopédie de Hegel où le corps du signe est comparé à la pyramide égyptienne. Le a de la diffrence, donc ne s’entend pas, il demeure silencieux, secet et discret comme un tombeau : oikesis.”Marges de la Philosophie, Jacques DERRIDA, 1968

Plans and section

Wednesday, November 5, 2008

Permanent exhibition layout

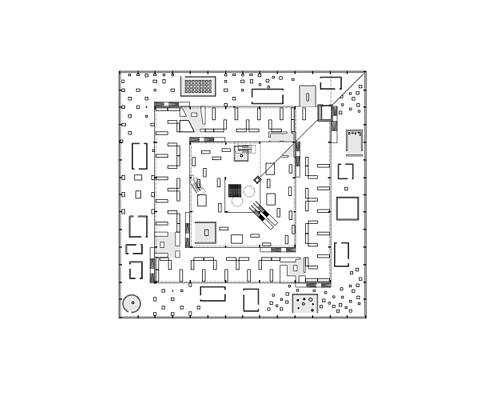

1) the museum's permanent exhibition layout is organised along a single spiral timeline, narrating the discovery of otherness, from Ethnocentrism (on the top) to the so called french Multiculturalism (on the lowest part).

2) the transversal exhibition, the most mobile part of the museum, sits on the lowest part of the spiral and cut through the building, linking separate geographical zones.

3) the museum's path ends back in the lobby, through the News and Library areas.

Saturday, November 1, 2008

Tower of Babel

Construction of the Tower of Babel, Hendrick van Cleve III (1525-1589/Belgian),

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Tower of Babel (Hebrew: מגדל בבל Migdal Bavel Arabic: برج بابل Burj Babil) is a structure featured in chapter 11 of the Book of Genesis, an enormous tower intended as the crowning achievement of the city of Babilu, the Akkadian name for Babylon. According to the biblical account, Babel was a city that united humanity, all speaking a single language and migrating from the east; it was the home city of the great king Nimrod, and the first city to be built after the Great Flood. The people decided their city should have a tower so immense that it would have "its top in the heavens." (וְרֹאשׁוֹ בַשָּׁמַיִם). However, the Tower of Babel was not built for the worship and praise of God, but was dedicated to the glory of man, with a motive of making a 'name' for the builders "Then they said, 'Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves; otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.'" - Genesis 11:4. God seeing what the people were doing, gave each person a different language to confuse them and scattered the people throughout the earth.

Thursday, October 30, 2008

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

Monday, October 20, 2008

Encyclopedic plateaus

The huge glass and steel structure of the Crystal Palace is built by Joseph Paxton to shelter the 1851 London World Fair, where the state of the art in science from around the world is brought together for the first time. The building is organized along what Mari Hvattum and Christian Hermansen call the Axis of Progress.

Entering the Crystal Palace though the south transept, the visitor encountered a twofold starting point; the beginning of the exhibition itself and the "point zero" of human civilisation. From South to North along the central transept of the palace he would progress through various degrees of "primitiveness" — from Tunis, through China and the Middle East, to India, Turkey and Egypt. The developmental line continued in the main nave, where the visitor was led, east to west, from the new world, through the European coninent, and finally to the conceived culmination of the exhibition and culture alike — the industrial products of the British Empire. The Great Exhibition was a carefully choreographed exercise in progressive historiography.

in Tracing Modernity: Manifestations of the Modern in Architecture and the City, Mari Hvattum, Christian Hermansen, Routledge, 2004

Here, space and time are compressed into one single narrative, where (non-Western) contemporary societies are understood as primitive steps of human evolution. Rather than of a geographic journey, the experience proposed to the public here is one of a time-travel. There is no Other, only different degrees of accomplishment.

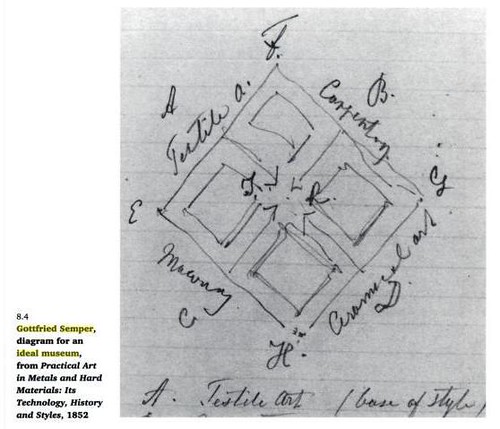

A very similar diagram is proposed by German architect Gottfried Semper (1805-1975) for his Ideal Museum. Attentive observer of "primitive" societies, driven by the idea that Art, rather than witnessing a cultural evolution, synthesizes an evolution of techniques, he outlines his Ideal Museum as such : pieces are grouped by medium, each group along a evolution axis that would go from the periphery to the centre of the museum, from the less developed technique. Here as well, time and space are compiled into one single narrative, with the least concern for cultural contexts.

The universal collection would form a great comparative matrix in which the artefacts were arranged not according to chronology of aesthetic value (the most common criteria for museum classification at the time), but according to the four primordial techniques of making, and their corresponding "elements". The section comprising textile art, for instance, would begin with the simplest wickerwork, expand to more defined textile products, and culminate in the metamorphosed motif of Beklidung in its different guises" […] The "complete and universal collection" was meant to provide a comprensive overview of human making. It would be not simply another museum but a complete encyclopaedia of human culture : a system of axioms by means of which a science of art could be established."

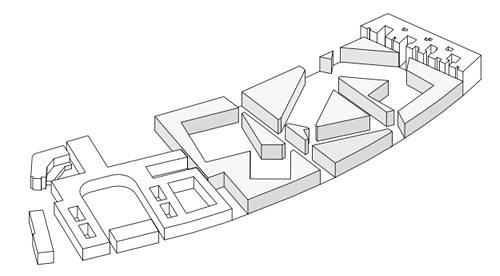

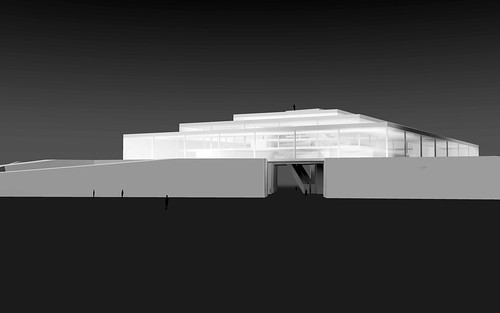

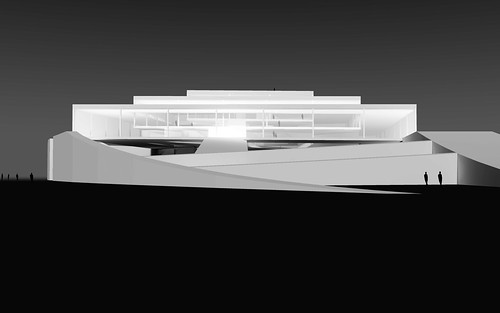

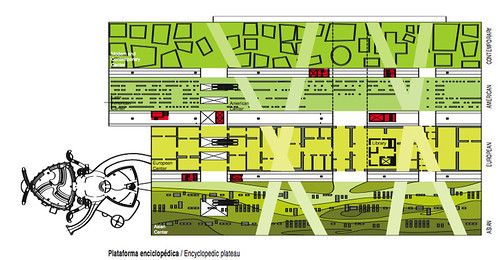

Not far, in some respect, from the above mentioned modernist universalist fantasies, the encyclopedic plateau proposed by OMA for the LACMA in 2004 is yet divided in four geographic/thematic stripes, each of them separated from the others by deep circulation trenches, and organized along its own timeline (History), at is own speed. Through transverse paths, visitors are invited to experience diachronisms and synchronisms in the collections.

Sunday, October 19, 2008

Saturday, October 18, 2008

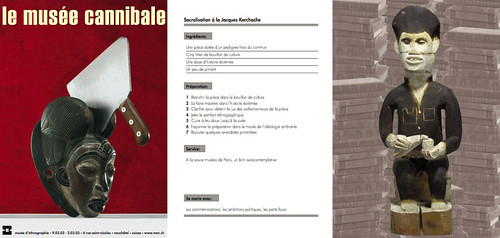

Musee cannibale

Sous le titre Le musée cannibale, l'équipe du MEN consacre son exposition temporaire au désir de se nourrir des autres qui a présidé à la création et au développement des musées d'ethnographie.

Constituées au fil des années par une succession d'acquisitions et de missions de collecte sur le terrain, les collections des musées d'ethnographie témoignent du désir d'incorporer une altérité d'autant plus valorisée qu'elle semble radicale.

Pour alimenter les visiteurs de leurs expositions, les muséologues extraient de leurs réserves des bribes de culture matérielle qu'ils apprêtent sur la base de recettes contrastées destinées à présenter tel ou tel aspect d'une similarité ou d'une différence entre l'ici et l'ailleurs. Ils dressent la table de cérémonie qui permet la consommation d'un lien social avec l'humanité tout entière. Ils en viennent même parfois à se consommer eux-mêmes à travers une mise en scène de leur propre pratique ou de leur propre regard.

Mais toujours ils s'interrogent sur les liens que les questions identitaires entretiennent avec la violence et le sacré, territoires hantés par la pulsion cannibale, à la fois communion sacrificielle, création symbolique et mode de lecture de l'autre.

Sunday, October 5, 2008

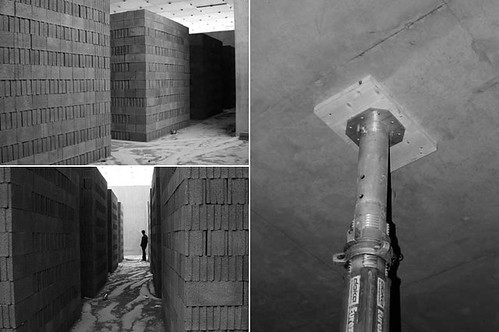

Museum's endangering publicness

Removal of a museum's glass window,Santiago Sierra

Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle, Belgium. September 2004

More photos HERE

All the Museum's glass windows were removed and the security equipment disconnected, including cameras and alarms. This forced the transfer of the museum's modern art collection and the protection of the office area.Description of the installation / performance, as given on Santiago Sierra's website

292 tons of concrete bricks were carried to the top floor of the Kunsthause Bregenz and the weight distributed on temporary supports through the whole building. Since 300 tons is the maximum wight the structure of the building can sustain, the number of visitors permitted at any time was never allowed to exceed 100, which represents an additional 8 tons.Description of the installation / performance, as given on Santiago Sierra's website

Zizek on multiculturalism

Why are so many problems today perceived as problems of intolerance, rather than as problems of inequality, exploitation, or injustice? Why is the proposed remedy tolerance, rather than emancipation, political struggle, even armed struggle? The immediate answer lies in the liberal multiculturalist’s basic ideological operation: the ‘culturalization of politics’. Political differences - differences conditioned by political inequality or economic exploitation - are naturalized and neutralized into ‘cultural’ differences, that is into different ‘ways of life’ which are something given, something that cannot be overcome. They can only be ‘tolerated’. This demands a response in the terms Walter Benjamin offers: from culturalization of politics to politicization of culture. The cause of this culturalization is the retreat, the failure of direct political solutions such as the Welfare State or various sociapost-political ersatz.Tolerance as an ideological categroy, Slavoj Zizek. in Critical Inquiry Volume 34, Number 4, Summer 2008

© 2008 by The University of Chicago. 0093-1896/08/3404-0009$10.00. All rights reserved.

Text available online HERE

Tuesday, September 30, 2008

Le Corbusier's Tower of Babel

Otlet regarded the project as the centerpiece of a new 'World City' — a centrepiece which eventually became an archive with more than 12 million index cards and documents.

If the task was already huge when Otlet developped his ideas, the later evolution of medias made impossible the target to be met. But some consider Mundaneum a forerunner of the Internet.

The Mundaneum in Mons, Belgium. More photos on dalbera.club.fr/mons/mundaneum/index.htm

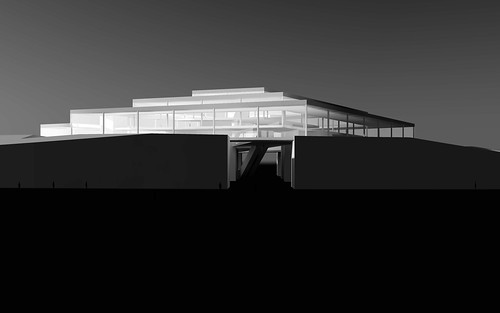

The Mundaneum in Mons, Belgium. More photos on dalbera.club.fr/mons/mundaneum/index.htmOtlet commissioned architect Le Corbusier to design a Mundaneum project to be built in Geneva, in 1929. Drafts were made for a whole city on the hills of the swiss capital. The World Museum, centerpiece of the complex, was meant to narrate, on a single chronological axis going from prehistory to today, an all-encompassing description of Human creation, by indifferently displaying pictures, original objects or facsimiles.

This project is the first, at least in diagram-plan, using the Spiral-museum typology, later recurring in a few Le Corbusier's museums. Its main feature is the very rigid and introverted corridor-shaped chronological exhibition path, going from the centre of the spiral and top of the building, towards its periphery, reaching the groundfloor at its end.

Witnessing the differend : a grammar

As a site of acknowledgement to Non-Western societies, often unknown by the public, the Musée du Quai Branly is the expression of France's will to give the right place to Primitive Art in its institutions. Further, it testifies there is no more hierarchy between arts than between peoples.Text as appears at the exit of the Pavillon des Sessions exhibitionThe concept of Art, as experienced in western culture, is far from being universal. In doesn't balance Western and "primitives", or "first" cultures. Rather, it assimilates the non-western World. While aiming at weakening the colonial dominant/dominated dialectic, our beatific admiration for primitive Arts actually gives it a new form.

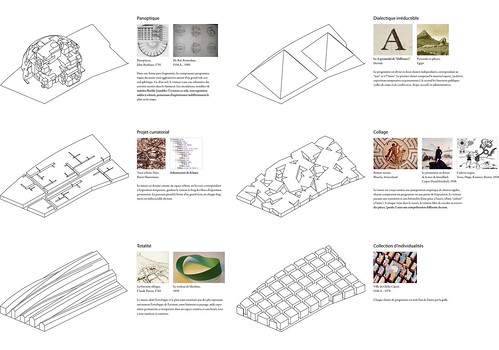

A few typologies, reinforcing and making dialectics such as subject/object, self/other, dominant/dominated, art/ethnology, explicit, are tested on the site.

From left to right and top to bottom- Panopticon

- Irreductible dialectic

- Curratorial project

- Collage

- Overwhelming totality

- Collection of individualities

Monday, September 29, 2008

The statue says :

Left : Place de la Concorde Paris Auteur : GIRAUD Patrick

Right : ©musée du quai Branly (Paris, Place de la Concorde, Easter Island statue)

Comparable pictures. Comparable situations ?

On the left : one of the obelisks set on Place de la Concorde, Paris. They were offered to France by egyptian Vice-King Mehemet Ali in 1830. In exchange of the obelisks, France offered a clock, which orns, since then, Cairo's Citadel, but never actually worked. The other Obelisk (which was never brought in France) was officially given back to Egypt by President Mitterrand.On the right, an advertisement for Quai Branly Museum's opening. To our knowledge, the statue on the collage never left Easter Island. But it is virtually taken away from its space and time (its authenticity, according to Benjamin), cleaned from its original meaning, and put in the middle of the piazza as a monument. The asterisk, recurring in the museum's communication, is giving it a voice. And oh, surprise ! the statue speaks french.